Written on: May 1, 2022 by Nicholas Georges

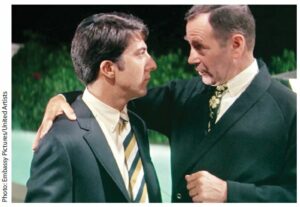

In 1967, Walter Brooke told Dustin Hoffman in the classic film The Graduate that “There’s a great future in plastics. Think about it. Will you think about it?”

Fast forward to 2022 at the resumed session of the 5th United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA-5.2), where 193 UN Member States endorsed a resolutioni to negotiate an international legally binding treaty by 2024 to fight plastic pollution.

Plastics offer a number of benefits, including being durable, lightweight and relatively easy to manufacture to fit a number of applications, far beyond just the realm of product packaging. However, without proper waste management, plastics are often considered the “poster child” for our waste issues, especially when countries such as China are no longer accepting imports of U.S. waste and we can no longer proceed with an “out of sight, out of mind” mentality.

The UN treaty on plastic pollution is expected to address the full life cycle of plastics, which includes design, production, consumption and waste management. Support for the design of reusable/refillable, re-manufacturable and recyclable products and materials, as well as minimizing waste generation, is expected to be included. The treaty is also expected to include ways that the private sector, along with other stakeholders—such as governments and non-governmental organizations—can take action to achieve treaty objectives.

In the first half of 2022, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) will establish an Intergovernmental Negotiation Committee (INC) responsible for developing the plastics treaty and will conduct a meeting to prepare for the INC’s work, including discussion of its timetable and organization. The first INC session will take place in the second half of 2022 in conjunction with a stakeholder forum that UNEP will convene to share knowledge and best practices from around the world related to plastic pollution. The INC’s work is expected to be complete by the end of 2024, at which point the UNEP will hold a diplomatic conference to adopt the treaty and open it for signature by national governments.

Part of the challenge with plastic waste is what can be done with it. While all plastics can be recycled, current recycling infrastructure is not set up to recover quality material from certain types of plastics. Some plastics pose unique challenges due to their structure. For example, flexible films have issues with current sortation processes and can get stuck in machines. Multi-material plastic items are difficult to recycle due to the inherent challenges with separating out the different types of plastic used. Further, since different types of plastic requiring different recycling processes may appear similar, there is confusion among consumers about how/what can be recycled. This increases contamination in what’s collected for recycling and, as a result, decreases the amount of material that can be recovered and the quality of what is recovered.

These challenges are relevant for plastics recycled via mechanical processes, where the plastic is physically broken down in order to transform it into new products. Mechanical recycling is by far what’s most widely used in the U.S. and what most current infrastructure is set up to handle. However, recycling plastic through mechanical processes weakens the strength of the plastic, limiting the number of applications the recycled resin can go into.

Another approach that has recently been gathering attention is advanced recycling, sometimes called chemical or molecular recycling, which uses a variety of technologies to break down plastic into its component chemicals (ex. the monomer) that are then used as building blocks to make new products and material. Advanced recycling provides recycled material that is as strong as its virgin counterpart and can process multi-material plastic items and mixed plastics with no issue. There are a number of stakeholders that are skeptical of the use of such technology, primarily driven by the fear that it’ll be used only to convert used plastic to fuel and pollute the world through air emissions when the material is burned for energy. Increasingly, though, advanced recycling is being used to convert waste plastics into virgin-quality plastics and recognized as a critical contributor to making the plastics life cycle more circularii.

Even if the supply of quality recycled material gets built up, it still needs an end market in order to displace virgin plastic. Companies are coming out with goals to have certain levels of post-consumer recycled (PCR) content, but Government is also coming out with mandates to require certain levels of PCR in plastic packaging. New Jerseyiii and Washington Stateiv have already passed laws and several other Statesv are looking at similar legislation. While these requirements are well-intentioned, they can be problematic. If they push the required levels too fast without addressing fluctuations in supply, the typically higher presence of contaminants and/or lack of knowledge about potential contamination, and the structural weaknesses associated with recycled plastics and supply isn’t able to keep up with demand, a price bubble will occur, putting a heavy cost burden on companies that will likely get passed onto their customers.

In just a few decades, the conversation has shifted dramatically from “plastics as key to technological progress” to “plastics as the villain hurting our planet.” It’s possible to utilize the technological benefits of plastic in a more sustainable way, but only if we address the problem of plastic waste. One tool increasingly being used is the displacement of virgin plastic in products and packaging with recycled content. This can have a significant impact on plastic pollution but requires further build-up of both the supply of recycled material with needed functionalities and robust end markets for that recycled material to make it competitive. With the UN’s endorsement of a resolution to negotiate a global treaty on plastic pollution, there is considerable uncertainty around what the plastic regulatory landscape will look like a few years from now. It’s important for businesses to stay up-to-date on the latest developments and ways to respond to the plastic waste challenge.

To discuss further or to get involved, contact us at ngeorges@thehcpa.org and mblessing@thehcpa.org. SPRAY

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

i The resolution to End Plastic Pollution: Towards an Internationally Legally Binding Instrument can be found here.

ii See, for example, Google and AFARA’s 2022 report Closing the Plastics Circularity Gap, available here.

iii link

iv link

v Includes Connecticut, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Rhode Island and Vermont.